Key Takeaways

- As heatwaves (and wildfires!) become more frequent, many schools are still ill-equipped to deal with the effects of extreme heat and poor air quality on students and educators.

- According to the U.S. General Accounting Office, roughly 36,000 schools across the country need to replace or update their heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems.

- Educators and their unions have been advocating at the local, state and federal level to highlight the importance of healthy indoor air quality and secure the funding necessary to upgrade school HVAC systems.

The school building that houses Adelaide Elementary School in Federal Way, Washington, is more than 65 years old. With no heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) system, and classrooms and offices all having single-pane windows, the school is not equipped to insulate students and staff from extreme heat. In the northwestern United States, where temperatures in May don't often exceed 70 degrees, that usually has not been much of a concern.

In May 2023, however, the region was gripped by a stifling heat wave that brought record-shattering temperatures.

Federal Way Public Schools was largely unprepared to deal with a situation that what soon became a crisis for many students and educators. Because of the magnitude of the heatwave, even those schools with some sort of working HVAC system couldn't keep their learning and working spaces at a comfortable temperature.

“Our buildings didn't get a chance to cool down,” says Shannon McCann, a special education teacher and president of the Federal Way Education Association (FWEA). “Everyone—students and staff—were suffering.”

Educators were tasked with finding ways to alleviate the heat, but there is only so much they could do. The impact on students was immediate and alarming.

Sara Rowe is the office manager at Adelaide Elementary. During the heatwave, no school nurse was on duty, so Rowe and a data secretary had to step in. They saw students who were close to passing out, suffering from nose bleeds, headaches, and increasing anxiety. “We had a young girl with a panic attack,” Rowe recalls. “The heat was making it feel as if the walls were closing in on her.”

Eventually, Rowe and her colleagues asked parents to take their children home. “I’m not a trained health professional, so it was very difficult dealing with these problems,” Rowe explains. “And because of security concerns, we're not allowed to keep windows and doors open. There was no way to get that air flow.”

It’s not just the Pacific Northwest. Due to high heat and saddled with infrastructure in dire need of repair or upgrade, school districts across the country have also been left with little options other than to send students home.

Closing schools because of high heat should be “unthinkable,” says Joseph G. Allen, director of Harvard University's Healthy Buildings Program and Associate Professor at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

“We’ve been in the sick building era for over 40 years, and we've neglected our school buildings. It’s just something we’ve tolerated, and I’m not sure why. We know that good ventilation and filtration are key to student health, student thinking, and student performance, and yet closing schools has become our new reality.”

The Heat is On

A June 2020 report by the General Accounting Office (GAO) estimated that 41 percent of public school districts need to replace or update their HVAC systems in at least half their schools —roughly 36,000 schools across the country.

The absence of working HVAC systems is even more alarming considering that rising temperatures due to climate change could cause even more uncomfortably hot days in classrooms in the near future.

In a 2022 study, the Center for Climate Integrity estimated that by 2025, there will be a 39 percent increase since 1970 in the number of school districts that see 32 or more days over 80 degrees . Furthermore 1,815 districts—serving 10.8 million students—will see three more weeks of school days over 80 degrees in 2025 than they did in 1970.

Rising heat can also fuel wildfires, which produce a wide range of harmful pollutants. The recent fires in Canada, which have blanketed the Midwest and East Coast with hazardous levels of pollution this week, were exacerbated by the heatwave that gripped the Northwestern U.S. in May. Wildfire smoke has forced many schools to cancel all outdoor activities

“What this smoke does to our air quality—combined with the extreme heat—only makes this issue all the more urgent for our schools,” McCann says.

When 90-degree days began to take hold in mid-May, however, the response from Federal Way district leaders was, to say the least, underwhelming.

“Sitting in a school that feels like a sauna has a devastating impact on students,” says Rowe. “We saw it every day, but we were told to think outside the box, be creative. We didn't really feel supported.”

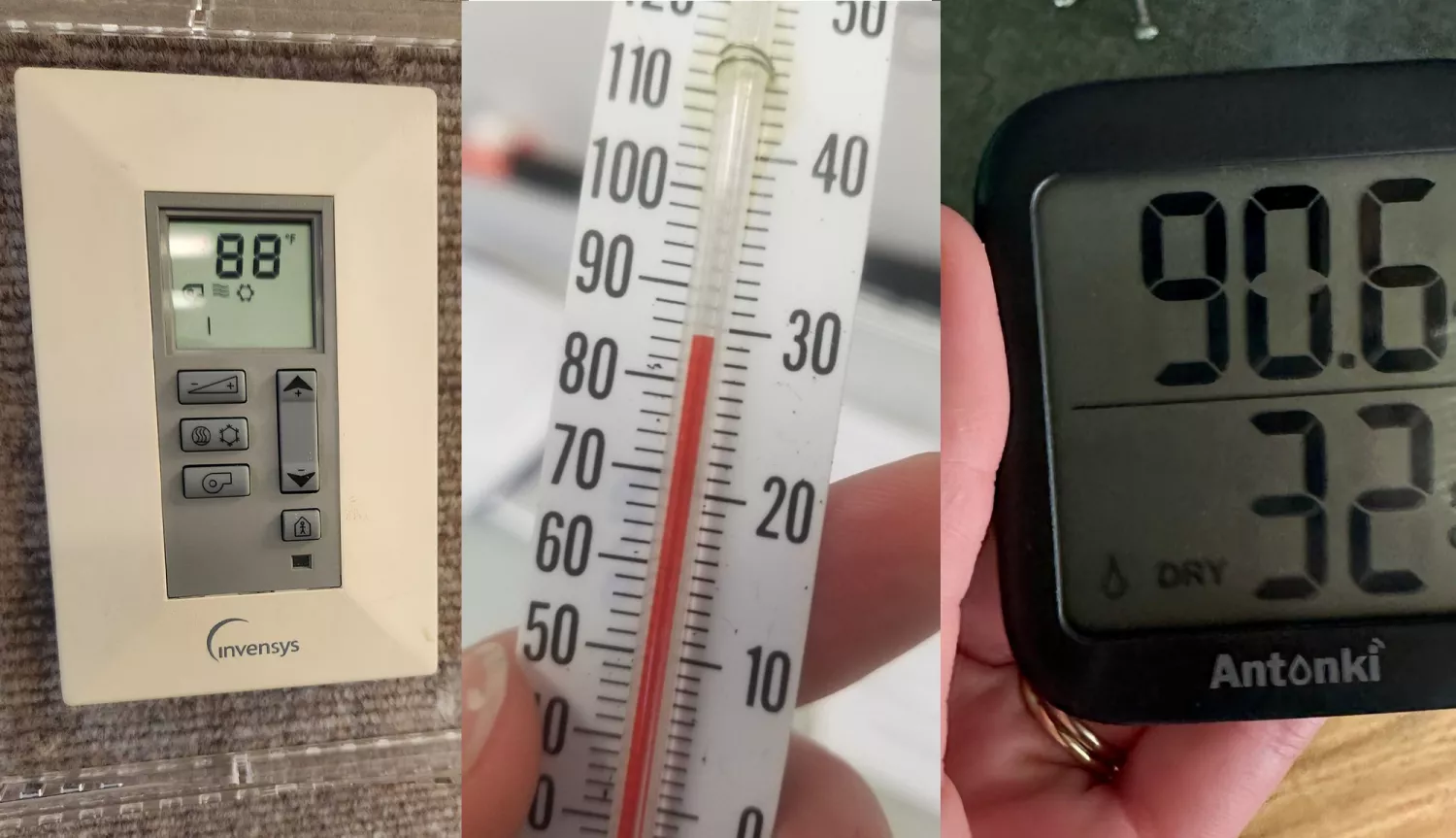

As she began to organize FWEA’s members, McCann asked educators to take photos of the thermostats in their work area and post them on social media—not that those unbearable temperatures actually violated district standards.

That’s because very few school districts have mandated temperature maximums. “The absence of standards …means we are allowing kids to sit in 95-degree classrooms leaving students unable to concentrate on learning due to high heat and humidity levels,” said Connecticut Education Association President Kate Dias.

And the devastating effects heat and poor indoor air quality (IAQ) has on student health, learning and behavior has been well-documented by a growing body of research.

A study published in the Nature Human Behavior journal in 2020 revealed that students scored increasingly worse on standardized tests each school day where the temperature rose above 80 degrees Fahrenheit. A 2023 study by Harvard University found that extreme temperatures also exacerbate absenteeism and student disciplinary referrals. This increase in disciplinary referrals on hot days were “driven entirely” by students attending schools without air conditioning.

Another study examining the impact on student achievement also connected those dots. “Air conditioning appears to offset nearly all of the damaging impacts of cumulative heat exposure on academic achievement,” Harvard researchers wrote in 2018.

Who’s Impacted the Most?

But heat doesn't affect all students the same way.

“Like many other aspects of society, we see gross inequities by race, ethnicity, and income when it comes to our schools,” Joseph Allen says. “Ventilation rates in schools are low to start with, and even lower in schools with predominantly Black and Hispanic students, and in schools with a majority of students on free or reduced fee lunch programs.”

Generally, more affluent parents are better positioned to reduce the academic effects of hot classrooms on their children with home air conditioning, or paying for a tutor after school. The Harvard researchers concluded that heat effects accounted for up to 13% of the U.S. racial achievement gap.

Federal Way Public Schools is a high-poverty district, so educators understood that closing school and sending students home wasn't necessarily going to offer significant relief.

“This is a multifaceted issue that is disproportionately affecting our students of color," McCann says. "During heatwaves, schools are no reprieve. So their standardized testing results, which we had to conduct this year in stifling temperatures heat and already an inaccurate measure, will be affected not only by the poverty they live in, but also by a heatwave that produced horrible learning and working conditions and that our schools weren't prepared for.”

Educators Take the Lead

"When we think about education," Allen says. “We think about curriculum and teaching, and lunch and recess, and transportation and socialization, but the role of the school building is an afterthought. The school building is as essential to learning as all of those other factors.”

Despite the ongoing challenges, Allen sees opportunities and momentum to make school buildings healthier for all students.

A historic opportunity arrived in the form of the American Rescue Plan (ARP), signed into law in 2021 to help the nation recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. The ARP—which NEA members and activists, through their tireless advocacy, helped secure—set aside nearly $170 billion for public schools, the single largest-ever investment in education funding.

According to a recent report by the Center for Green Schools, school districts prioritized a significant amount of the available funding to pay for costly HVAC upgrades and support indoor air quality for their students and staff—the second-highest category for district planned spending, behind staffing. (Learn more about these critical funds and how you can determine their use in your district.)

CEA has been a tireless advocate for cleaner IAQ in schools for many years and was ready to work with leaders at the local and state level to fund upgrades. In 2022, CEA helped secure $150 million dedicated to HVAC improvements in schools. Half of those funds are coming from ARP and half will be from state bond funding. In April, the state announced the first round of schools—many in low-income areas—to receive funding for new upgrades.

In 2022, educators in Hawaii, led by the Hawaii State Teachers Association (HSTA), successfully lobbied for passage of a bill that appropriates $10 million to the Department of Education to install air conditioning units in public school classrooms that do not have them. The bill will address the needs of roughly 20% of the 5,000 classrooms in the state that are without such systems. “More needs to be done to complete this task,” HSTA President Osa Tui, Jr., told lawmakers. “Our students, teachers, and staff are still suffering.”

Educators are also using the power of collective bargaining. The lack of working HVAC systems for all classrooms was a driving factor in the Columbus Education Association's vote to strike last August. Last September and October, Columbus, Ohio had a combined 14 school days over 80 degrees and roughly one-quarter of schools there don’t have air conditioning.

After striking for three days, educators agreed to a new contract that, among other highlights, won a guarantee that all student learning areas will be climate-controlled no later than the start of the 2025-26 school year, including the installation of HVAC units in every school building.

‘It’s Not Sustainable’

As soon as educators in Federal Way started sounding the alarm about overheated classrooms, FWEA contacted state lawmakers, who then notified the governor about potential emergency funding to equip all schools with air conditioning. Schools don't break for the summer until June 21. “And then we have summer learning,” McCann says. “Many of our ESPs work for up to 11 months. We've had to send them home before and will probably have to again.”

Ultimately, McCann believes making schools climate-resistant should be the goal, and that requires local, state, and federal collaboration.

“This is a problem that can no longer be left up to individual districts. It's just not sustainable. We'll work with them, and our members will continue to push, but politicians and legislatures need to address this issue now. Too many people don't think about the effects of heat until it gets here. Then it’s too late, because when when a heatwave comes, the impact is so debilitating.”